KARCHER STAFF BLOG

2018-2019 Karcher Calendar

Facebook Page: https://www.facebook.com/KarcherMiddleSchool/

BASD Staff Blog: https://basdstaffnews.blogspot.com/

2018-2019 Karcher Calendar

Facebook Page: https://www.facebook.com/KarcherMiddleSchool/

BASD Staff Blog: https://basdstaffnews.blogspot.com/

______________________________________________________________________________

Kudos

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________

- Kudos to Dustan Eckmann, Liz Deger, and Laura Gordon on a great Strings Festival this past Tuesday! Beautiful - and thanks for letting my girls help you clean up a bit!

- Kudos to all of our staff for your efforts and kind words about and for our students during the Karcher Character Awards. Thank you as well to Stephanie Rummler and Brad Ferstenou for putting together the fun activities during both assemblies as well and for the spirit week set up!

- Thank you to Donna Sturdevant, Stacy Stoughton, Rod Stoughton, Dustan Eckmann, Mike Jones, Suzanne Dunbar, Cynthia Orzula, and Stephanie Rummler for assisting with the Snoco Activities this past Friday night! It was a great night for our students! Thank you to Jodi Borchart for also coming to assist as well!

- Last week we had interviews for our new Karcher lead engineer. Starting on Monday (tomorrow) Josh Oldenberg will be starting and replacing Harvey Kandler. Josh has always wanted to work for BASD and oversee one of our buildings. If you see him please welcome him to BASD and to Karcher! His office area will be in room 105 (where it was before) in case you want to introduce yourself!

Article of the week:

This is a continuation from last week - when thinking about what questions to ask during guided instruction ("We do it") below are some great ways to think about questioning.

Guided Instruction ("We do it")

Chapter 2. Questioning to Check for Understanding

What Is a Robust Question?

Many of the questions that a teacher poses during the course of a day's teaching are couched in a common classroom discourse pattern know as Initiate-Respond-Evaluate (Cazden, 1988). In an I-R-E questioning cycle, the teacher asks a question, elicits a response, evaluates the relative quality of the answer, and moves on to the next cycle. It goes something like this:

Teacher: How many sides does a triangle have? (Initiate)

Student: Three. (Respond)

Teacher: Good. (Evaluate) How many sides does a rectangle have? (Initiate)

An I-R-E questioning cycle is not inherently bad. After all, one role of a teacher is to evaluate the nature of the response. However, if the intent is merely to sort the correct from the incorrect, evaluation is reduced to simply keeping score. In addition, we would argue that the quality of the question in the preceding example is pretty low, particularly if the types of questions within the exchange never rise above recall of facts. Further, if the intent is to control rather than probe, this questioning technique is not going to result in much benefit for either the teacher or the student.

On the other hand, a robust question is one that is crafted to find out more about what students know, how they use information, and where any confusion may lie. A robust question sets up subsequent instruction because it provides the information you need to further prompt, cue, or explain and model. In particular, you want to determine the extent to which students are beginning to use the knowledge they are learning. In keeping with a Gradual Release of Responsibility model, the expectation is that students are still at an early stage and are not yet at the level of mastery. If students are able to answer robust questions thoroughly, then that is an indication that they are ready to further refine their understanding in the company of peers, especially through productive group work (Frey et al., 2009). We have grouped the major types of questions used in guided instruction into categories. Some questions elicit information, some invite students to link previous knowledge to new information, and some encourage further elaboration or clarification. In addition, robust questioning requires students to problem solve and to speculate.

Elicitation Questions

These form the backbone of questioning for guided instruction because they draw on skills and concepts that have been previously taught. These foundational questions provide the teacher with a baseline from which to work. A student who is unable to respond to an elicitation question is likely to need more direct explanation and modeling. Elicitation questions can focus on finite knowledge ("What is the name of the protective case a caterpillar makes as it becomes a butterfly?"). Conversely, an elicitation question might require application-level knowledge ("Why does the chrysalis need to be hard?"). The variable here is what has been initially taught during a focus lesson. That lesson may have been composed of what Bloom (1956) describes as knowledge- and comprehension-level understandings, or perhaps it consisted of application- or synthesis-level knowledge. When asking an elicitation question, the teacher's purpose is to gauge what the student has retained through instruction to this point.

For example, after 9th grade English teacher Kelly Johnson introduced her students to persuasive techniques using direct explanation and modeling, she asked them a series of elicitation questions. As she displayed print advertisements on the screen, she instructed her students to identify the techniques used. She showed them a popular ad from the Marines that read, "The few. The proud. The Marines." Her students correctly identified this as including a "glittering generality." Because she had modeled providing the rationale, she asked them to justify their answer. Olivia said, "It's got really powerful emotional words in it, like proud."

Elicitation questions can also be posed to unearth misconceptions. When 5th grade teacher Zach Eloy asks a small group of his mathematics students to estimate their answers before calculating the equation 3/8 × 1/2 = _____, he is listening for whether they anticipate that the answer will be larger or smaller than the numbers they began with. Although he has introduced this concept using a think-aloud process so his students could witness how he uses his mathematical reasoning, he is not sure whether this group has yet reached this understanding. His purpose for posing this elicitation question is to see if these learners still cling to the misconception that multiplication always results in a larger number.

Divergent Questions

These questions require students to couple previously taught information with new knowledge. There's a ladder effect going on here. Much like a person using a lower step to hoist himself onto a higher one, some types of knowledge are built in a similar fashion. The Reading Recovery program refers to this as using knowledge "on the run"—that is, applying previously learned information to figure out something new (Clay, 2001). When kindergarten teacher Ming Li asks her students to transform the word goose to loose using the magnetic letters she has arranged on the whiteboard, she is asking them a divergent question, and she is observing how they are using what they know about the letter-sound relationships and the way words work to construct a new word.

Elaboration Questions

Some robust questions come as a follow-up probe to an initial question. An elaboration question is used to find out more about a student's reasoning. In particular, these questions invite students to extend their response by adding ideas. For example, 11th grade chemistry teacher Al Montoya pauses at the desk of Edress and reads the student's lab sheet over his shoulder. Mr. Montoya points to the third question, which asks Edress to make a prediction about what will occur when a piece of zinc metal is added to a salt solution and an acidic one. Noting that Edress has written, "I don't think anything will happen to the metal," Mr. Montoya says, "Tell me more about this prediction. Why do you think nothing will happen to the zinc?" By asking Edress to elaborate on his response, Mr. Montoya is probing the reasoning his student is using to support this prediction.

Clarification Questions

As with elaboration questions, which often come after an initial response, clarification questions invite students to extend their thinking by requiring them to provide a clear explanation. A clarification may be genuine, as when the teacher truly doesn't understand a student's response. In other cases, the clarification question is used to further expose student understanding about a concept. In her 7th grade social studies classroom, Cindy Seymour routinely asks clarification questions during guided instruction. "I always remind [students] that they need to 'think like a historian,' so they have to provide evidence. 'Because' is a big word around here." During guided instruction on the narratives of formerly enslaved people in their Southern state, Ms. Seymour asks her students to draw a powerful image of the passage their collaborative learning group read and discussed. When Brandi displays her group's drawing of a whip, Ms. Seymour poses a clarification question, asking them to provide a direct quote from the reading.

Heuristic Questions

The term heuristic may be unfamiliar, but what it represents is not. A heuristic is an informal problem-solving technique, sometimes described as a rule of thumb. Our guess is that you have developed heuristics for where to park your car at the mall, choosing a checkout line at the grocery store, and hosting a large family gathering. It's likely that you did not learn these techniques formally, but instead developed them over the years through experience and conversation with others. In classrooms, heuristics refer to the academic problem-solving techniques students use to arrive at a solution. For example, a commonly taught heuristic in mathematics is to draw a visual representation of a word problem to visualize the operation. When 1st grade teacher Marilen Cervantes asks her mathematics students how they keep track of objects they are counting, she is posing a heuristic question. When 10th grade world history teacher George Boyle asks a student to use a graphic organizer of her choice to show the political alliances during the imprisonment of Mary, Queen of Scots, by Elizabeth I, he is posing a heuristic question.

Inventive Questions

An inventive question requires students to use their knowledge to speculate or create. Again, the emphasis is on using information that students have been recently taught in order to create something new. Fourth grade teacher Beth Kowalski asks Ronaldo, who has just finished the latest installment of the Time Warp Trio series by Jon Scieszka and Lane Smith, to make a recommendation about who might like the book. This inventive question requires Ronaldo to consider what he knows about the series and to combine that with newer knowledge on developing book recommendations. Twelfth grade English teacher John Goodwin asks Shaudi to tell him how Ayn Rand's Anthem (2009) helps her to answer the school's essential question, "Can money buy happiness?" Like Ronaldo, Shaudi has to integrate what she knows about different topics and situations to answer the question.

Figure 2.2 presents a summary of the various types of questions. In addition to these, there are specific types of questions that relate to texts that students are reading. We'll explore these four types of questions next, then turn our attention to creating a system for using questions.

Figure 2.2. Types of Questions to Determine Student Knowledge

Type of Question

|

Purpose

|

Examples

|

|---|---|---|

Elicitation

|

To unearth misconceptions and check for factual knowledge

|

|

Divergent

|

To discover how the student uses existing knowledge to formulate new understandings

|

|

Elaboration

|

To extend the length and complexity of the response

|

|

Clarification

|

To gain further details

|

|

Heuristic

|

To determine the learner's ability to problem solve

|

|

Inventive

|

To stimulate imaginative thought

|

|

Frey, N., & Fisher, D. (2010). Identifying instructional moves during guided learning. The Reading Teacher, 64(2). © 2010 by the International Reading Association. Adapted with permission.

| ||

______________________________________________________________________________

Information/Reminders

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

- Monday, February 11 - 7th grade to the auditorium after announcements/attendance to go over scheduling for the 2019-2020 school year.

- Please bring them up when you complete announcements/attendance... we will not make announcements for houses, etc. Just come up!

- Monday, February 11 - iReady Training for our academic, special education, and interventionists. Those listed first in the list below please secure a sub for the training (again)... sorry!

- We will start at 8:10 in the 21st Century lab with 8th grade going first until 11:10. Then 7th grade will start at 12:00 - 3:00. Please be on time and have your sub plans set according to this schedule - 8th grade teachers please note, in your plans, where the subs should go after they are done with you. They will all be taking lunch at 11:24 but then their 5th hour will start at 11:56 in _____ person's room.

- Here are the pairings for our subs:

- Sturdevant/Hancock

- S. Rummler/Botsford

- Geyso/Murphy

- Jones/Tenhagen

- Weis/Berezowitz

- Schmidt/Ferstenou

- K. Rummler/Smith

- Stoughton/Jorgenson

- Riggs/Varnes

- Riggs.. we will have you attend with 7th in the afternoon

- Fulton/Thate

- Ebbers/Zeman

- Newholm/Bekken

- Monday, February 11 - Candygram Sales begin!

- Tuesday, February 12 - Continuation of iTime rotation.

- This rotation will end on March 1 with new iTime groups starting on March 5.

- Tuesday, February 12 - Special Education department meeting @ 2:40 - 3:15

- Wednesday, February 13 - No PLC (TWT)

- Wednesday, February 13 - Due to the iReady training taking place until 3:00 on Monday lets have BLT meet during our usual PLC time from 2:40 - 3:20 so that we can discuss iReady online, ALL, and Forward Exam schedule. Along with what readings for next time!

- Friday, February 15 - 8:00 - 4:00 inservice day.

- We will start in the library to touch base about our Essential Skills as we start to think about the 2019-2020 school year. Then everyone will work on your essential skills from 8:00 - 12:00. Ryan and I will move around the building to touch base with teams.

- Then you have teacher work time from 1:00 - 4:00.

______________________________________________________________________________

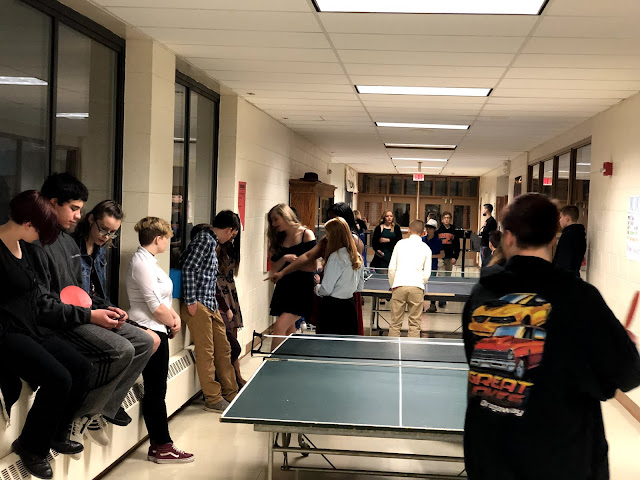

Pictures from the week