Karcher 2017-2018 School Calendar

Students of the week!!!!!!!

(Running slide show)

The students of the week are now posted as you come up the stairs to the main office and as you go down the stairs between the art and science classrooms. Thank you to Stephanie Rummler, Harvey Kandler, and our student council students for your efforts and awesome display!

______________________________________________________________________________

Kudos

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________

- Wow we had a lot going on this last week!

- Kudos to Steve Berezowitz and Jodi Borchart for your work and presentations with all of our students about proper social media use! The presentations were very well done!

- Thank you Marian Hancock for your assistance with our MAP makeup students throughout the last few weeks and into this week!

- Thank you to our advisory team, Jack Schmidt, Eric Sulik, and Wendy Zeman for your help setting up the Danish Invasion for our 7th grade students! It was well received and always a great opportunity for our students.

- Kudos to Barb Berezowitz, Andrea Hancock, and our 7th grade staff team for a well done 7th grade School Forest field trip! Students and outside chaperones had a great time!

- Great job to Mike Jones and Donna Sturdevant for your work with our first FNL! Thank you also to the following staff who volunteered to assist for the night: Amanda Thate, Kris Thomsen, Patti Tenhagen, Stephanie Rummler, Kurt Rummler, Steve Berezowitz, Erika Fons, and Joshua Audenby.

______________________________________________________________________________

Information/Reminders...

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

- Social Studies teachers... it is your week to have students email their parents/guardians about the learning that has been taking place within your class!

- Science teachers will be giving the Reading MAP test this week in their classrooms.

- Monday, October 2 - Staff meeting in the library.

- The focus is on the October 9 - 13 extended advisory information and needs.

- Monday, October 2 - Cross country meet at BHS for our Karcher students.

- Wednesday, October 4 - Essential Skills PLC.

- Thursday, October 5 - Girls home basketball game!

- Friday, October 6 - TSID forms are due to Grace Jorgenson. If you have any questions please see Grace!

Reminder...

- 4 Mandatory Trainings for ONLY the individuals on the document below.

Pictures from this past week!

Some great work being done during iTime this past week where the focus is on ELA and math throughout the building through targeted instruction.

Students with Ms. Stoughton working on additional practice with algebraic equations.

Students with Ms. Sturdevant working on coordinates and finding slope.

Students with Ms. Riggs making connections within their novels by using actual puzzle pieces to show the connections.

Mr. Ferstenou and Ms. Botsford's classrooms utilized the article below with the focus around questioning and the skill of debating.

Outside of iTime we are in the swing of things and had a busy week!

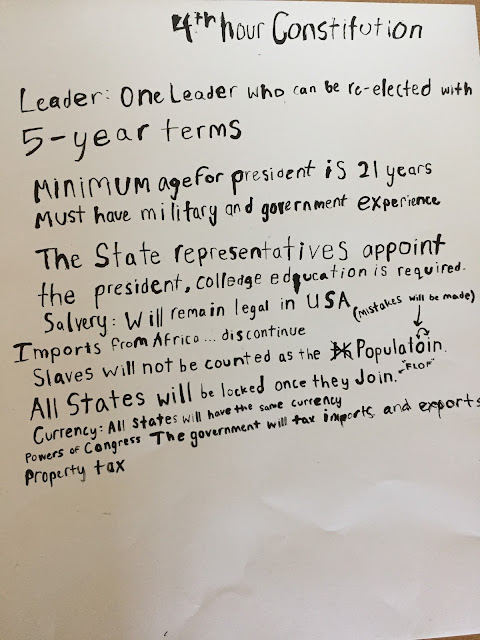

Students in Ms. Rummler's class reenacting the Constitutional Convention of 1787. All students portray members of the Convention and debate the issues from the stand point of the state they represent. In the end, they create a Constitution based upon the laws they have been able to agree upon.

All students met with Mr. Berezowitz and our police liaison officer, Jodi Borchart, to discuss concerns and proper use of social media devices and the impact of our actions and words on others.

Students in Ms. Murphy's classroom working on an annotating strategy by reading for two minutes then noting items of importance in the margin. Reading for another two minutes, annotating, and repeat. Students then exchanged their marked up text with each other to determine what type of annotation the mark up was.

Danish Invasion this past Thursday within our 7th grade advisory groups! Both the Danish students and our students did a great job! Always a positive when we can give our students additional cultural experiences!

Our first FNL for the 2017-2018 school year was a success! Around 120 students in attendance!

Continuation from last week... REALLY GOOD READ and centered around higher-order thinking and student engagement.

Some great work being done during iTime this past week where the focus is on ELA and math throughout the building through targeted instruction.

Students with Ms. Stoughton working on additional practice with algebraic equations.

Students with Ms. Sturdevant working on coordinates and finding slope.

Students with Ms. Riggs making connections within their novels by using actual puzzle pieces to show the connections.

Mr. Ferstenou and Ms. Botsford's classrooms utilized the article below with the focus around questioning and the skill of debating.

Outside of iTime we are in the swing of things and had a busy week!

Students in Ms. Rummler's class reenacting the Constitutional Convention of 1787. All students portray members of the Convention and debate the issues from the stand point of the state they represent. In the end, they create a Constitution based upon the laws they have been able to agree upon.

All students met with Mr. Berezowitz and our police liaison officer, Jodi Borchart, to discuss concerns and proper use of social media devices and the impact of our actions and words on others.

Students in Ms. Murphy's classroom working on an annotating strategy by reading for two minutes then noting items of importance in the margin. Reading for another two minutes, annotating, and repeat. Students then exchanged their marked up text with each other to determine what type of annotation the mark up was.

Our first FNL for the 2017-2018 school year was a success! Around 120 students in attendance!

Continuation from last week... REALLY GOOD READ and centered around higher-order thinking and student engagement.

Total Participation Techniques: Making Every Student an Active Learner, 2nd Edition

Chapter 2. A Model for Total Participation and Higher-Order Thinking

The TPT Cognitive Engagement Model and Quadrant Analysis helped us to dramatically change our methods of teaching. Previously we had attempted activities that we thought would engage our students during class. … Analysis of these activities made us realize that our activities were more in quadrants one and two than in three and four.

P. Witkowski and T. Cornell

In this chapter, we will focus on two tools you can use to plan for cognitively engaging teaching. The first, the TPT Cognitive Engagement Model, will present a way to assess the quality of the teaching and learning that is happening within classrooms. The second, The Ripple, provides a way to visualize approaches toward posing deep prompts and questions in a way that cognitively engages every student.

Consider the effort your brain requires to respond to the following task: Define human rights. For most people this task requires that they simply dig into their mental files, find an adequate definition, and complete the task by articulating the definition. Adequately responding to this task does not require a deep analysis of the concept and what the concept entails. On Bloom's cognitive taxonomy, it would be considered a lower-order question.

Now consider the effort your brain would require to answer this question: How has your perception of human rights been affected by your culture and your country's history? To successfully answer this question, you have to dig quite a bit further. You have to locate cognitive files on what you know about human rights, your culture's perceptions of human rights, how people's perceptions of human rights have changed over time, how other cultures view human rights, and how your perceptions might have differed if you had been born in a different culture or before certain historic events in your own country. Answering the question requires analyzing, making connections, drawing conclusions, and basing those conclusions on what you know about historic events and the resulting societal changes. On Bloom's cognitive taxonomy, this would be considered a higher-order question. It requires that you flex your cognitive muscle, and make numerous cognitive connections between what you've learned and what you already know.

Creating classroom opportunities for developing higher-order thinking is essential for helping students become the critical thinkers, problem solvers, innovators, and change makers upon which every society thrives. In writing this book, we wanted to be careful to make sure that TPTs were not simply used as another way of getting one-word answers or answers that would be considered superficial knowledge from students. With all of the TPTs, we need to aim for deeper learning, because a teacher can use an activity that ensures total participation but still perpetuate the lower-order thinking that might have been present in a traditional question-and-answer session. Except for the fact that all students are answering, a teacher could implement TPTs ineffectively and only require that students regurgitate forgettable facts. Our goal is to move students beyond shallow and superficial understandings and toward learning that is cognitively intense, meaningful, and deep. Note that Bloom's cognitive taxonomy, lower- and higher-order thinking, and Webb's Depth of Knowledge are further explained in Appendix A.

Ensuring Higher-Order Thinking

The use of prompts that require higher-order thinking is what takes students beyond simple engagement. It ensures that students are cognitively engaged. Students aren't just engaged and having fun; they are also thinking deeply. The need to emphasize higher-order thinking is why we felt compelled to include sections on "How to Ensure Higher-Order Thinking" for most of the techniques presented. Student interaction will only be as powerful as your prompts. So take the time to develop prompts and activities that require students to reflect and analyze, evaluate, and synthesize their learning. Be sure that you provide opportunities for students to explore the big picture in lessons and justify responses based on concepts learned.

Done well, TPTs can require that students make connections from the classroom content to real life. This process works best when teachers have thought through the big picture of their lessons and understand what is most important for students to walk away with. Your students will not remember everything you try to teach them, just the meaningful parts, so focus on deep meaning. In this way, relevance will be made transparent to your students. What is the big picture in your content objectives? How can you make it relevant? Through the act of ensuring higher-order thinking, you engage children in thinking through the implications and the relevance of the content to their world. They are looking intently within the nuances of the conceptual understandings so as to be lost in connection making. Like the student quoted at the end of Chapter 1, whose problems seem to go away when she comes to class, we want children to get "lost" in the learning.

The TPT Cognitive Engagement Model

The TPT Cognitive Engagement Model (see Figure 2.1) is aimed at helping you visualize the relationship between total participation and higher-order thinking in your classroom. Evidence of learning will occur when students are actively participating and developing higher-order thinking, as is the case when activities fit into Quadrant 4 in the model. Although all of the quadrants may reflect important aspects of your teaching, be sure to shift back to Quadrant 4 throughout your lesson to allow students to process and interact regarding the learning.

Figure 2.1. TPT Cognitive Engagement Model and Quadrant Analysis

Teaching that gets stuck in Quadrant 1 (Low Cognition/Low Participation) is problematic for several reasons. What evidence is there that students are processing what was taught? Because the content is using lower-order thinking, how important is it and how long will it stick? Are students perceiving this content as relevant? What is going on in their minds as they sit and pretend to listen to the teacher?

Teaching that lingers in Quadrant 2 (Low Cognition/High Participation) allows students to review and often apply what they have learned, but frequently what they have learned is easily forgotten because it is not linked to anything deep. Because it required high participation, it may have been fun; but because it required only lower-order thinking, it also was very forgettable.

Teaching that lingers in Quadrant 3 (High Cognition/Low Participation) may be an improvement from Quadrant 1, but for whom? Teaching that is predominantly represented in Quadrant 3 is selective in requiring evidence of higher-order thinking only from certain students. An article titled "The 'Receivement Gap'" (Chambers, 2009) addresses the inequity in access to high-quality educational opportunities. Chambers argues that the achievement gap is largely due to unequal access to high-quality learning experiences for students tracked into classrooms with fewer learning opportunities. We believe that a receivement gap also exists within classrooms when we operate predominantly in Quadrant 3. The students who always participate and have their hands up are the ones who benefit from the higher-order questions prepared by the teacher. If your lessons tend to linger in Quadrant 3, TPTs can ensure that all of your students are benefiting from the higher-order thinking that currently only a few are experiencing.

It is important that we structure our teaching so that every lesson includes several opportunities for all students to demonstrate active participation and cognitive engagement in what we are teaching. Activities in Quadrant 4 (High Cognition/High Participation) allow us to obtain evidence of this. Although there will be times when we want to make sure students comprehend basic understandings necessary to get them to higher-order thinking, our ultimate goal is that students be able to analyze, evaluate, and synthesize what they've learned. This goal is what keeps us moving back to Quadrant 4 periodically throughout our lessons.

Consider using the quadrants in Figure 2.1 to analyze your planning. As you work with teams or instructional coaches, consider asking a peer to observe you. In which quadrants did you tend to linger? Could a question have been better posed through a TPT to ensure that all students benefited rather than just a select few?

We encourage you to use the TPT Cognitive Engagement Model to analyze your own planning, as well as to help you support your colleagues in their teaching. If you are an administrator, the model can also help you in supporting your teachers in their planning or as you analyze lessons that you observe. A reminder poster containing an image of the Cognitive Engagement Model quadrants is included in Appendix B. Additional resources and a professional development activity can be found on our website at www.TotalParticipationTechniques.com.

The Ripple

In Chapter 1, we described what we called "the beach ball" scenario, where a teacher poses a question to the whole class and calls on a handful of volunteers who choose to respond. One of the consequences of the beach ball scenario is that after a teacher has gone through the trouble of creating great prompts aimed at higher-order thinking, only a handful of students get to demonstrate that they have processed the question. To ensure that all students are reflecting on and responding to the prompt, we encourage teachers to "ripple" their questions (Himmele & Himmele, 2009). Rather than using the traditional question-and-answer approach where a teacher poses a question to the class as a whole, rippling begins with every student responding (individually) to a prompt, then sharing that response in pairs or small groups, followed by volunteers sharing with the class. We call this a ripple because it starts with the entry of a pebble into water—also known as your question or prompt—to which every student individually responds. The next ripples move outward from the student's individual response into pairs or small groups, and finally the ripples reach the whole group.

In most traditional question-and-answer sessions, teachers skip the individual reflection time, which would allow for deeper learning on the part of every individual student. Instead of starting with the whole group, keep every student accountable for learning by structuring your prompts so that every student is given an opportunity to individually reflect on and react to the prompt. This can be by way of Quick-Writes, Quick-Draws, or other techniques suggested in Chapters 4 through 8. This individual reflection time is important for all students, even if it's only two minutes long. Then the ripple moves outward when you ask students to join up with a peer (see Figure 2.2) and share and interact regarding their responses to the prompt. The outer ripple appears as you ask pairs to join existing pairs, or as you open up the floor to the larger class, eliciting responses once students have had time to bounce ideas off each other. Now that students have shared and met with success with their peers, they will be more likely to respond in a larger group. One thing is certain: students are not likely to respond with the dreaded "I don't know" after you've given them the opportunity to reflect individually and then in small groups. By rippling your questions and prompts, you ensure that all of your students are reflecting on prompts aimed at higher-order thinking.

Figure 2.2. The Ripple

Allowing students time to individually collect and record their thoughts, and then rippling outward with Pair-Shares or small groups before bringing them to the whole class, provides students the security of having already met with success. Sixth grader Ariel shared her appreciation for the way Quick-Writes and Pair-Shares were implemented using this ripple approach: "I liked it because you get to share your feelings with one person instead of saying them in front of the whole class." Socially tentative students are not the only ones who will benefit; students with certain special needs and English language learners will especially benefit from using the Ripple, which gives them time to process their own thinking individually and then in pairs or small groups, laying the groundwork for them to feel comfortable enough to share their thoughts with the class.

When reading student reflections regarding her unit on imagery, metaphors, and symbolism, Keely Potter noted that "some of the big trends that students touched on, the comfortable and safe environment, was what I noticed from the get-go." Meghan Babcock agreed and said, "And that was because of our structures and our protocols that ensured that all students have a voice in a nonintrusive way—the Quick-Writes, the Pair-Shares, the Chalkboard Splashes. … The safety and the community came so much from these little structures of total participation being built in." A reminder poster aimed at helping you remember to ripple is included in Appendix B.